SLAB Cache Organization

Slab based memory allocation is a mechanism to provide efficient allocations for commonly used data structures that has been implemented in a variety of UNIX derived operating systems. Linux is among the *NIXs that uses the slab allocation method and actually provides a few variations. I will be covering just the basic slab system however there are others including the slub system which is a variation intended to improve performance and reduce metadata overhead.

To begin with; what is a slab allocator?

Conceptually slab allocation is very simple, set aside some pages in memory designated for providing allocations of a specific size. The size of an object within a slab is usually based on the size of a commonly used kernel data structure. A few common examples of a structs that are allocated from a slab cashe are inodes, dentries, buffer_heads, and many more. The primary advantage to this methodology is a significant reduction in fragmentation of allocated memory as well as reducing the complexity of attempting to find an available chunk of memory for to satisfy the request.

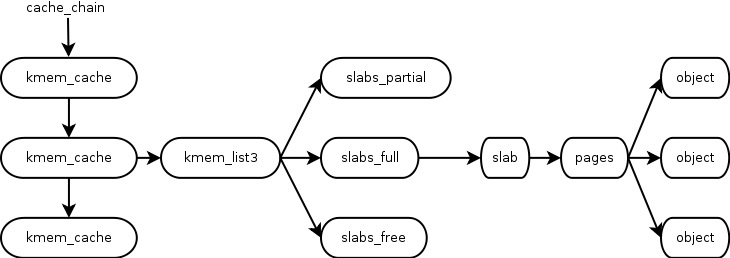

Organization of the slab cache

(hurray for dia… starting to get the hang of that app)

(hurray for dia… starting to get the hang of that app)

Starting at the top is cache_chain a linked list containing all of the caches currently in existence. Each entry is a kmem_cache struct that organizes a cache for one size of object. Each kmem_cache contains an list of slabs for each NUMA node defined as an array of kmem_list3 structs. kmem_list3 contains 3 (could you guess?) lists of slabs for the cache; slabs_partial, slabs_full, and slabs_free. Each list is use to make decisions when servicing requests for a new object. slabs_partial is the list of slabs that are (wait for it) partially full and is the first place to look when allocating a new object. If there are no more free objects in a slab it gets moved to slabs_full, and if slabs_partial is empty slabs_free is checked for an available empty slab to be used.

Each struct slab within the 3 lists is a group of contiguous pages (quite often 1) and is the size a cache can be grown or shrunk. The process of keeping track of what objects within a slab are in use will be the subject of a future post. Each slab contains a different number of objects depending on the size of the object and the number of pages in each slab.

Creating and Destroying slabs

As objects are allocated and deallocated the number of slabs in slabs_free will change. When there are no available slabs in slabs_free a new slab must be allocated which is done by the cache_grow() function. cache_grow() kmalloc’s (indirectly) enough pages for the given slab from the NUMA node for the corresponding kmem_list3 struct, sets up the struct slab and attaches it to the slabs_free list. The slab system sets up a workqueue on each cpu to shrink caches by calling the cache_reap() function. cache_reap() walks down the cache_chain list and attempts to free pages associated with slabs in various slabs_free lists. This process happens every few seconds and is designed to keep the slabs_free lists from holding onto pages for too long. Another time that caches are “reaped” is when kswapd is attempting to free up some memory if the overall system memory is getting low.

Final Thoughts

This has been a relatively light overview of the slab system and while there is a lot left out it serves as a good jumping off point for further articles on the subject. To poke around the slab cache on your running system you can cat the proc knob /proc/slabinfo which contains a list of all of the existing caches and a number of interesting statistics about each one.